"A room without books is like a body without a soul. If you have a garden and a library, you have everything you need." -Marcus Tullius Cicero

Sunday Essay

As I was putting sticky notes on multiple pages of a reference book I use often, I found myself thinking about physical books, libraries, and respect.

The book in question is a working reference which I bought used more than ten years ago. It came with some damage, yet it is of good quality with smooth, fine paper, clear printing, and heavy cover stock. It is what I believe is referred to in the trade as a quality paperback. I often make notes in the margin in pencil. I riffle through it casually while holding a pen, and flop it over when opened to a certain page I am using. It is a tool, a workhorse, and I do not pamper it.

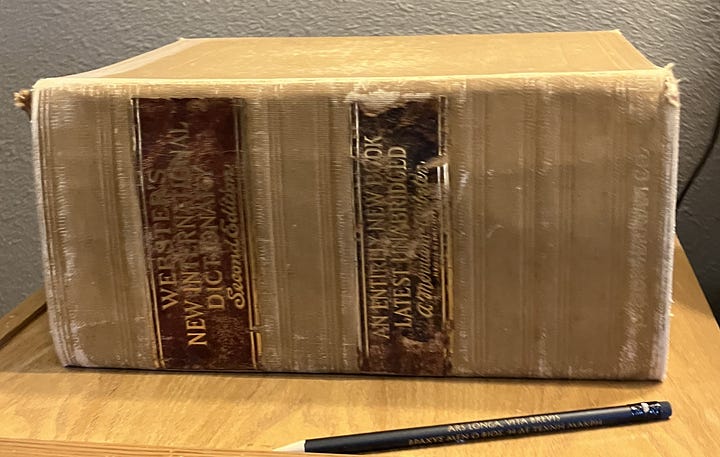

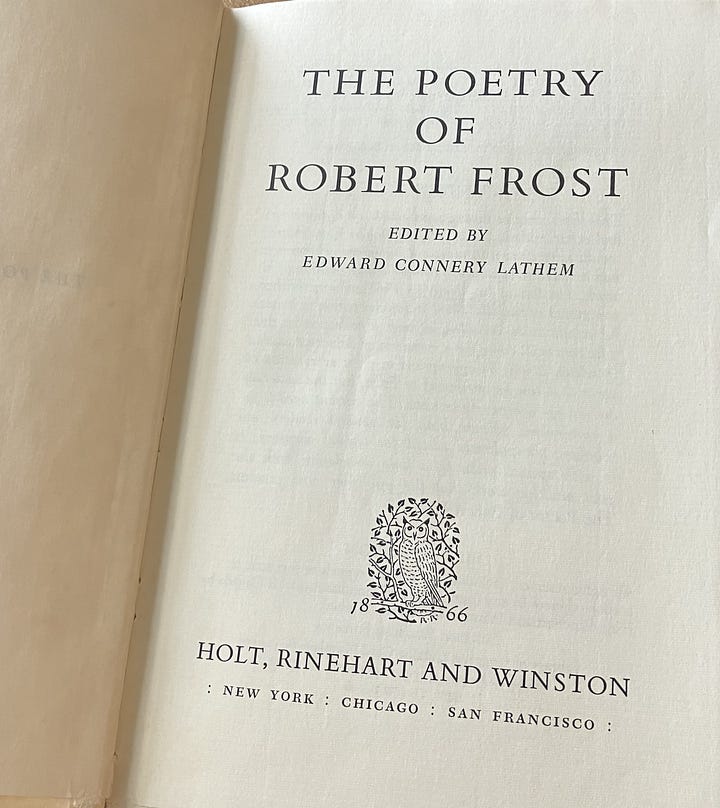

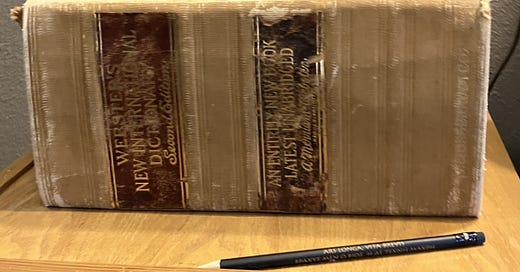

However, I would never treat other books this way. Obviously, the “coffee table” books are handled quite differently. For starters, they are not put on the coffee table unless they are being actively read—and that only after clearing away beverages. Otherwise, large hardcover books with beautiful images on coated paper have always been kept safely on a shelf which cannot be accessed by pets, children, wine, coffee, food, candles, or direct sun. The same goes for specimens that are very old, fragile, or have sentimental value, such as my Webster’s New International Dictionary — An Entirely New Book — Latest Unabridged, ©1934; or my first edition hardcover, The Poetry of Robert Frost, edited by Edward Connery Lathem, which I carried with me through high school. Caring for these friends is easy, and the rules are clear. But I also have quality paperbacks bought new in the 1970s with intact spines, great covers, and no damage to the pages — all of which have survived an overseas move as well as dozens of cross-country and local moves.

If I buy a used book printed on poor quality “pulp” paper, I do my best not to add to the damage, but I don’t worry too much about how I handle it. It will not have a long life, will yellow and then brown at the edges, become brittle, and the glue will dry out and crack before too long. I know people who regularly dog-ear pages in this type of book, so assuming they actually own the book, this does not bother me. Although I might disagree with the treatment of other types of books by people, how other people handle any of the books that they own is not my business.

I was raised to revere books, and taught how to handle them. In our home we were expected to wash food, dirt, or grease off our hands before handling books. We were shown how to reach up to the top right corner and gently separate the page for gentle turning. Books were never to be jerked open, cracking the spine, nor were they ever thrown, no matter how immediate the need for ammunition against a brother’s sneak tennis ball attack (in fact, we had determined that the real function of our mother’s ubiquitous coasters was not as furniture protection, but as defensive projectiles).

Before we could read, we were reminded to keep food and liquids away from books, use bookmarks, and set books back on the shelf when finished. Later, chapter books were put on a desk or night stand where they were easily accessible but not in the path of damage.

By instruction and by example, books were handled as items of value intended to last indefinitely, and they were esteemed as friends.

The first day of second-year Latin in middle school, Mr. Doogan distributed brand new textbooks. Brand new textbooks were so rare that we were actually excited—nerdy little eggheads that we were—feeling oh-so-special, sniffing the heady aroma of new-book glue and paper, and clearly unaware of the hours and hours we were destined to spend with Ulysses, grinding through declensions and conjugations, puzzling over vocabulary and obscure references as we translated book-after-book-after-book-oh-lord-Homer-get-a-life-and-please-get-this-guy-back-to-Ithaca-already. No internet, and no English translations anywhere.

But I digress. Back to the new textbooks. We spent the first 30 minutes of class being instructed on how to handle a new book, preparing it for use so as not to break the spine. We were shown how to lay it on its spine, and beginning with the covers, take a few pages from the front and back of the book simultaneously, easing them down to the desk, until reaching the center.

Now, there is nothing I like better in a library book than to see signs of repeated use with reasonable care: a worn cover, that velvety edge that pages sometimes take on with age and handling, and a respectable bit of ambient, accidental dirt. An old book which has served a community for years and continues to interact with readers is a gem, and also what we should be able to expect. Where would that yummy library smell come from, otherwise?

However, there are rules about using books which are borrowed, whether from the library or from an acquaintance. It annoys me to find that someone has dog-eared a page, even in a pulp paperback. It rankles me when people routinely turn pages by using a thumb from the left hand to grope at the bottom edge of the right page near the binding, where it is common to see the resulting small tears and buckled paper from having done so.

It enrages me to see chocolate fingerprints in library books, while simultaneously hoping that it is, in fact, chocolate, and not something else. Pushing the page toward the binding or licking fingers to get a grasp on the next page? Disgusting. Writing in a library book tilts me toward apoplexy.

Hey, I get it that sometimes, we might spill, splash, or otherwise accidentally get a book dirty. I’m all for taking them to the beach, the park, on vacation, the bus: in short, wherever people go, with the caveat that this means taking extra care with more expensive books. I know that occasionally, a romance novel will slip and fall into the bathtub, oops! It happens. And what grownup people do is replace it by showing the library staff the damage you caused, and paying so that a new copy can be purchased. Full stop. It’s not unlike how people should behave in a shop: you break it, you buy it. It’s called being a responsible adult.

The careless, crass and disrespectful signs of a library book being treated like a pad of scratch paper, a catalog, or one’s own personal property, pisses me off.

First, it’s rude and inconsiderate.

Second, it is a sign of selfish indifference to community property.

Third, it shortens the life of a book, depriving others’ use of it.

Fourth, it is in effect, spending everyone else’s taxes to replace it after a shorter life span.

Fifth, it models to children that this is an acceptable way to behave.

Sixth, it offends my sense of how to treat books and one another.

So yeah, I know I’m likely preaching to the choir as the saying goes, but this extends to all the things we share and use in common. With books, though, there is a special kind of trespass I feel when they are abused. Thanks for letting me kvetch.

Not to end on a grouchy note, I found this quote:

Handle a book the way a bee does a flower, extract its sweetness but do not damage it. -John Muir

To me, books for the most part represent knowledge, and for that reason are to be treated at very least with respect. That includes even those containing ideas I disagree with. History shows that those who burn books generally regress to burning people.

Agree. Agree. Agree. Though must confess the cookbooks I’ve used most often kind of look like they’ve been through the kitchen wars. They have. And my highschool hardback of Moby Dick is heavily annotated in the margins - in ink.