Many are familiar with the song Kumbaya, whether from camp as a kid, or because of its ubiquity during the 1960s and ‘70s through artists such as Pete Seeger, Joan Baez, and the Weavers. More recent covers have been recorded by Sweet Honey in the Rock, Nanci Griffith, and Raffi in the United States; Joan Orleans in Germany; Manda Djinn in France; and the Seekers in Australia.

In about the mid-1980s, however, this cultural standard acquired a connotation of mocking for liberal causes and naïveté. The first documented instance of this change seems to have been in a movie review, as reported by the Dallas Morning News in a November, 2006 article, “Kumbaya: How Did a Sweet, Simple Song Become a Mocking Metaphor?”

An extensive…search of databases of newspapers, magazines and other sources turned up what may be the first ironic reference to "Kumbaya" in print, from Aug. 16, 1985.

The line is from a Washington Post review by Rita Kempley of the comedy movie Volunteers: "Tom Hanks and John Candy make war on the Peace Corps in Volunteers, a belated lampoon of ‘60s altruism and the idealistic young ‘Kumbayahoos’ who went off to save the Third World."

Eye-rolling cynics have since attached the song to any idea they perceive as unrealistic in order to derogate lofty ideas or consensus-building as insipid and soft-headed. Efforts to incorporate anti sexual harassment training into corporate America have elicited comments like “Next, we’ll all join hands and sing Kumbaya.” Any locus of tough-guy culture will be rife with resentful patriarchal attitudes at having to “waste time with this bullshit” and “have a Kumbaya moment.”

The reasons that Kumbaya became linked to nose-wrinkling derision might remain unclear as long as we look for logic. However, some years ago, before John Lewis’s death, I heard him briefly clarify the song’s cultural and historical significance, and wanted to look more deeply into its origin.

Where did the song originate?

What language is the word Kumbaya?

What does it mean?

There are several theories and claims about its origins.

In 1939, a White American composer and evangelist from New York City named Marvin Frey published and copyrighted sheet music for one version of the song, claiming it to be his original work. In a move that contradicted his own claim, he later stated that he wrote the words in 1936, based on a prayer he had heard from an evangelist in Oregon.

Yet by the 1940s, the song was a widely known spiritual among African Americans in the South.

Then in 1958, a group out of Ohio called The Folk-smiths recorded a version called “Kum Ba Yah,” writing in the liner notes that the song came from Africa via missionaries to Angola.

Where did this song come from?

Angola? The Pacific Northwest? New York City? Ohio? The South?

Is it American or African?

My research led to the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress. There, I learned that the earliest documented evidence of the song is in the archive of the AFC (American Folklife Center) in the form of a manuscript together with a recording made on a wax cylinder.

One of the earliest records of “Kumbaya” in the AFC archive is in a manuscript sent to Robert Winslow Gordon, the Archive’s founder, in 1927. The collector was Julian Parks Boyd, at that time a high school principal in Alliance, North Carolina. This version, which Boyd collected from his student Minnie Lee in 1926, was given the title “Oh, Lord, Won’t You Come By Here,” which is also the song’s refrain.

Although a section in the middle is inaudible, several verses at the beginning and the end …are enough to identify it conclusively as “Kumbaya.”

As far as we know, this cylinder is the earliest sound recording of the song, and it is therefore among the most significant evidence on the song’s early history.

You can hear it with this link

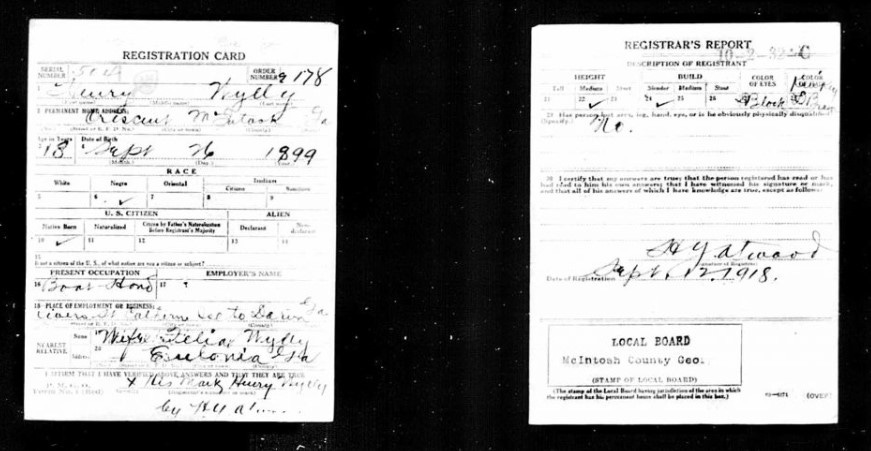

The recording is marked by Boyd as “sung by H. Wylie.” Archive staff believe that Wylie (or Wylly) is the same person whose draft card for World War I shows the following:

It shows his occupation as Boat Hand, and that he made "His Mark” instead of signing—which easily explains the Wylie/Wylly, as it was likely a difference due to phonetic spelling.

Of note is the residence of Mr. Wylie (Wylly) listed as Crescent, Georgia, in McIntosh County. Make a mental note of McIntosh County. Now, the interesting thing from a linguistic and human perspective is that the language listed in the archive for this recording shows: “Sung in ‘Gullah,’ or Sea Islands Creole Dialect.” This explains how “Come By Here” is heard and sung as “Kum Ba Yah,”—the word “yah” in Gullah dialect meaning “here.”

So, although the song “Come By Here” might have been known and sung as an African American spiritual in areas of the South prior to the nineteenth century, the unique emergence of “Kum Ba Yah,” based on my research, points to the isolated sea coastal islands where enslaved people spoke a rich dialect that combined English, multiple African languages, and the languages of slavers and traders.

The Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor website offers the following:

The Gullah Geechee people are descendants of Africans who were enslaved on the rice, indigo and Sea Island cotton plantations of the lower Atlantic coast. Many came from the rice-growing region of West Africa. The nature of their enslavement on isolated island and coastal plantations created a unique culture with deep African retentions that are clearly visible in the Gullah Geechee people’s distinctive arts, crafts, foodways, music, and language.

Gullah Geechee is a unique, creole language spoken in the coastal areas of North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia and Florida. The Gullah Geechee language began as a simplified form of communication among people who spoke many different languages including European slave traders, slave owners and diverse, African ethnic groups. The vocabulary and grammatical roots come from African and European languages. It is the only distinctly African creole language in the United States, and it has influenced traditional Southern vocabulary and speech patterns.

Religion and spirituality have a sustaining role in Gullah family and community life. Enslaved Africans were exposed to Christian religious practices in a number of ways and incorporated elements that were meaningful to them into their African rooted system of beliefs. These values included belief in a God, community above individuality, respect for elders, kinship bonds and ancestors, respect for nature, and honoring the continuity of life and the afterlife.

Did you know that every time you use the words “gumbo,” “yo,” “tote,” “bubba,” “yam,” “juke,” “jitters,” or “goober,” you are speaking Gullah?

Remember I said to make a mental note of McIntosh County, Georgia? The reason is because there happens to be a video of a concert given by the McIntosh County Shouters that gives texture and reality to the area where Mr. Wylie lived. If you’re hooked on this rich cultural story, here is the link to the concert. It is narrated by a member of the group, helping us understand the significance of the dance and music, which is performed by current Gullah-Geechee residents wearing authentic costumes.

What is Ring Shout?

From the McIntosh County Shouters website:

Ring shout’s roots go back to traditions common to Central and West Africa. The origins of the ring shout came with them when enslaved people were brought to America in the 1700s. Drums and drumming were not allowed on plantations in Coastal Georgia during slavery; plantation owners feared it could be used to signal an outburst or uprising. Instead, the Gullah-Geechee would keep the rhythm for percussion by clapping their hands, tapping their feet, and beating the floorboards with a wooden stick.

The stick man set the beat, then he or another male lead songster would begin to sing out the first lines of the shout. The women (shouters) moved in a counterclockwise circle, singing back or shouting the responses while pantomiming the lyrics.

Ring shouts often followed a church service. As a form of worship that blended both African and Christian elements, it was a way for enslaved people to honor their African ancestors and traditions. The shout also provided an essential form of communication for enslaved people to send messages to each other that the white plantation owners couldn’t understand.

There are dozens of topics and hundreds of related details radiating from this story. I have chosen to tell the story of Kum ba yah through the path that interested me, beginning with Mr. Wylie, tracing the elements historically, socially, linguistically, and culturally through the Gullah-Geechee people who still live in the area today.

The many variations of original words were and are light years away from the botched interpretations of misgruntled 20th- and 21st-century American Idiots (thanks, Green Day). The words are deeply haunting pleas for help by people stolen violently from their homelands; beaten, tortured, and raped; bought and sold as property; chained; worked to death; deprived of their children and families; stripped of human decency and basic care; and existing with no hope of anything changing. Ever.

A sampling of authentic pleas:

Someone sick Lord, kum ba yah (come by here)

Someone sick Lord, kum ba yah

Someone sick Lord, kum ba yah

Oh, Lord, kum ba yah.

Somebody moanin’ Lord, kum ba yah…

I’m gon’ need you Lord, kum ba yah…

Well we in trouble Lord, kum ba yah…

Someone’s dying Lord, kum ba yah…

Somebody need you Lord, kum ba yah…

Now I need you Lord, kum ba yah…

My intention is to shine light on the deep roots of this work of musical heritage forged in suffering. Perhaps by doing so, we can all help reclaim it from the popular nonsense which has relegated it to a tasteless, ignorant epithet, and restore it to a place of reverence through an understanding of its origins.

For more information on Gullah language and history

See the Smithsonian’s Anacostia Community Museum’s (downloadable pdf) publication, “Word, Shout, Song: Lorenzo Dow Turner, Connecting Communities Through Language.”

Lorenzo Dow Turner (August 21, 1890 – February 10, 1972) was an African-American academic and linguist who did seminal research on the Gullah language of the Low Country of coastal South Carolina and Georgia. His studies included recordings of Gullah speakers in the 1930s.

Thanks to subscriber of Closing the Loop for posting this timely article about the retirement of the last Gullah-speaking clergyman, from August 3, 2024 in the Guardian:

“The last Gullah sermon? End of an era looms for endangered language”

Thank you coming by the Verbihund Café.

Ways to support writing as a livelihood; each one is appreciated.

restack this post

send to a friend

share on social media

send to others who love words, language, and history

Thank you for this fascinating history of a song I grew up with. (I was a church camp kid.) I was aware of the Gullah dialect and artwork but not their connection to "Kumbyah." What is most striking to me is that the original lyrics and how the song was sung are the exact equivalent of the intercessory prayer in the Episcopal liturgy! And THIS is why I love the Library of Congress, the American Folklife Center in particular. I'm actually feel excited by what I've learned from your post!!

This is wonderful Kate! I have been singing this song all of my lif. I am unsure where I learned it, as it feels I have known it forever. I know I sang it in MYF, in a church get together, also in Girl Scouts and at my Girl Scout Camp. We knew a number of verses back then. :A lot great memories go along with the song

Thanks so much Kate for choosing this song today.